2 Ducat Netherlands Gold

1583, Netherlands, Zeeland, Philip II. Gold 2 Ducats Coin

Denomination: Gold 2 Ducats

Ruler: Philip II (Felipe II) of Spain.

Mint Period: 1581-1583 (not dated)

Mint Place: Middleburg (privy mark: tower)

Reference: Friedberg 300 ($2500 in XF!), Delmonte 878. R!

Diameter: 30mm

Weight: 6.89gm

Material: Gold!

Obverse: Cross (:+:) above crowned and draped vis-a-vis busts of Ferdinand V and Isabella (the Catholic Monarchs). Pseudo mint-initial (8-like S) in the middle surrounded by 4 pellets in the middle. Titles of Philip II as King of Spain and Count of Zelland around.

Legend: PHLS . D : G . HISP . Z . REX . COM . ZEL : . : (privy mark: tower) .

Translation: "Philip by the grace of God King of Spain & Count of Zeeland."

Reverse: Crowned shield with coat-of-arms of the Kingdom of Spain.

Legend: . DUCATVS CO . ZEL . VAL . HISP

Translation: "Ducat of the County of Zeeland... "

Philip II (Spanish: Felipe II de Habsburgo; Portuguese: Filipe I) (May 21, 1527 – September 13, 1598) was King of Spain from 1556 until 1598, King of Naples and Sicily from 1554 until 1598, king consort of England (as husband of Mary I) from 1554 to 1558, Lord of the Seventeen Provinces (holding various titles for the individual territories, such as Duke or Count) from 1556 until 1581, King of Portugal and the Algarves (as Philip I) from 1580 until 1598 and King of Chile from 1554 until 1556. He was born in Valladolid and was the only legitimate son of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V.

Philip II (Spanish: Felipe II de Habsburgo; Portuguese: Filipe I) (May 21, 1527 – September 13, 1598) was King of Spain from 1556 until 1598, King of Naples and Sicily from 1554 until 1598, king consort of England (as husband of Mary I) from 1554 to 1558, Lord of the Seventeen Provinces (holding various titles for the individual territories, such as Duke or Count) from 1556 until 1581, King of Portugal and the Algarves (as Philip I) from 1580 until 1598 and King of Chile from 1554 until 1556. He was born in Valladolid and was the only legitimate son of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V.

Under Philip II, Spain reached the peak of its power. Having nearly reconquered the rebellious Netherlands, Philip’s unyielding attitude led to their loss, this time permanently, as his wars expanded in scope and complexity. So, in spite of the great and increasing quantities of gold and silver flowing into his coffers from the American mines, the riches of the Portuguese spice trade and the enthusiastic support of the Habsburg dominions for the Counter-Reformation, he would never succeed in suppressing Protestantism or defeating the Dutch rebellion. Early in his reign, the Dutch might have laid down their weapons if he had desisted in trying to suppress Protestantism, but his devotion to Catholicism and the principle of cuius regio, eius religio, as laid down by his father, would not permit him to do so. He was a devout Catholic and exhibited the typical 16th century disdain for religious heterodoxy.

One of the long-term consequences of his striving to enforce Catholic orthodoxy through an intensification of the Inquisition was the gradual smothering of Spain’s intellectual life. Students were barred from studying elsewhere and books printed by Spaniards outside the kingdom were banned. Even a highly respected churchman like Archbishop Carranza, was jailed by the Inquisition for seventeen years for publishing ideas that seemed sympathetic in some degree to Protestant reformism. Such strict enforcement of orthodox belief was successful and Spain avoided the religiously inspired strife tearing apart other European dominions, but this came at a heavy price in the long run, as her great academic institutions were reduced to third rate status under Philip’s successors.

However, Philip II’s reign can hardly be characterized as a failure. He consolidated Spain’s overseas empire, succeeded in massively increasing the importation of silver in the face of English, Dutch and French privateers, and ended the major threat posed to Europe by the Ottoman navy (though peripheral clashes would be ongoing). He succeeded in uniting Portugal and Spain through personal union. He dealt successfully with a crisis that could have led to the secession of Aragon. His efforts also contributed substantially to the success of the Catholic Counter-Reformation in checking the religious tide of Protestantism in Northern Europe.

The Philippines, a former Spanish colony, are named in his honor.

(3191 X 1600 pixels, file size: ~1M)

Posted by: anonymous 2023-10-30

1583, Netherlands, Zeeland, Philip II. Gold 2 Ducats Coin. (6.89gm!) NGC AU-58! Denomination: Gold 2 Ducats Ruler: Philip II (Felipe II) of Spain. Mint Period: 1581-1583 (not dated) Mint Place: Middleburg (privy mark: tower) Condition: Certified and graded by NGC as AU-58! ...

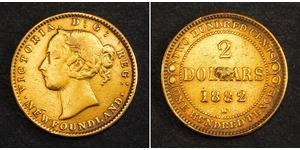

2 Dollar Canada Gold Victoria (1819 - 1901)

group has 39 coins / 38 prices

⇑