The Treasures of "Nuestra Señora de Atocha" The Ghost Galleon

The Ghost Galleon In the century following Columbus' dramatic voyage of discovery in 1492, the riches of her New World colonies helped make Spain the most powerful nation in Europe. Taxes on goods shipped from Central and South America by Spanish merchants enabled Spain to defend its Western Hemisphere claims against the English, French, and Dutch, and to extend its empire halfway around the world into the South Pacific.

The Atocha and its sister ship, Santa Margarita, are tragic milestones along this broad commercial highway (called Carrera de Indias by the Spanish) that carried Europe on a journey from isolation to world domination. Not only were the colonies prime consumers of goods produced in Spain; the conquests initiated a torrent of valuable agricultural goods, precious metals and high-quality gems that pulsed through the veins of Spanish mercantile shipping and back to the mother country. From 1530 to 1800, approximately six billion to eight billion dollars of gold and silver were mined in the Spanish American colonies. During this time, the ratio of gold to silver shipped to Spain was about one to ten. This wealth drastically changed the course of European history, raising Spain to a position of world dominance.

When 16-year-old Philip IV ascended the throne in 1621, he inherited an empire that controlled vast territories on four continents, a mission to purge Europe of the growing threat of Protestantism, and a huge national debt.

The trade with the Indies, and the taxes and revenues the Crown derived from it, were the financial lifeline which kept the Empire-and its staunch defense of Catholicism-afloat. The threats to this lifeline were legion. The Dutch openly attacked the Indies fleets. The English and French continuously challenged Spain’s claims in the New World. And internally, Spanish merchants engaged in smuggling, bribery, and deceit to avoid paying the quinto, a 20% tax levied on the proceeds of trade with the Indies.

In 1503, a regulatory agency was established to oversee every aspect of Spain’s trade with the Indies. Called the Casa de Contrastacion, it functioned both as ministry of commerce and official school of navigation. A clerk, or escribano, accompanied each vessel and maintained the official record of all cargo loaded and unloaded: the ship’s manifest. The manifest served as the basis for collecting the quinto and the averia, an additional tax, as high as 40% helped the government offset the cost of defending the merchant vessels that brought Indies wealth to Spain.

To discourage smuggling, the Crown decreed in 1510 that smugglers would forfeit their contraband and pay a fine of four times its value. Naval officers convicted of smuggling could be sentenced to several years as a galley slave. Despite the tough laws, it’s estimated that more than 20 percent of the gold and silver mined in the New World was smuggled back to Spain untaxed.

To minimize losses to armed raiders, Spain required all merchant ships to sail in convoys, which were protected by escort ships known as galleons. The galleons were a special type of warship, up to a hundred feet long and rigged with square sails. The profile was unmistakable, as the stern section of a galleon, called the sterncastle, soared up to 35 feet above the ship’s waterline, and was capped with the classic high poop deck. And the galleons were heavily armed, mounting huge bronze cannons. Although slower than the quick brigantines and sloops favored by pirates, the galleons possessed immense firepower. Still, perhaps five percent of the silver and gold mined by Spain in the New World was lost at sea or confiscated by pirates. In addition to the galleons sailing among the merchant ships in convoy, two strong galleons -a capitana, which led the group, and an almiranta, which brought up the rear-provided extra protection against English, French, and Dutch raiders. The convoys sailed from Spain in early spring and, upon arriving in the Caribbean, dispersed into groups to pick up heavy consignments of Royal treasure from various ports in the colonies.

Each fleet, or flota, had a specific destination. The Manila fleet sailed from the Philippines and delivered fine china, porcelain, silk, and other products of Spain’s trade in the Orient to Acapulco. The cargo was then transported overland to Veracruz, on the east coast of Mexico. At Veracruz, it was picked up by the New Spain fleet along with gold and silver from the Royal mint at Mexico City.

The Tierra Firme fleet was loaded in Portobello and Cartagena with silver and gold from Peru, Ecuador, Venezuela, and Colombia. Copper from the King’s mines in Cuba was added in Havana. The Honduras fleet called at Trujillo for valuable indigo dye.

When things went according to plan, all fleets met in Havana, Cuba in July to assemble the cargo for the voyage back to Spain. The bulk of the gold and silver was usually carried by the large, heavily-armed galleons, while the smaller merchant ships transported agricultural products.

Spain was still the preeminent power in 1622. However, her position of power was badly slipping as the crucial stages of the Thirty Years War unfolded. The year before, Spain had ended a 12-year truce with her rebellious Dutch provinces. The Dutch had joined with France, openly attacking Spanish naval and merchant vessels. The cost of the fighting sapped Spain’s economy, and the Royal Treasury was seriously overextended. To finance the war and continue the pomp and splendor of the Royal Court, the Crown borrowed heavily; so heavily that the king’s bankers kept representatives in Seville to claim a large share of the wealth when the rich convoys arrived from the New World each year.

Although the treasure fleet had sailed in 1621, money in the treasury was dangerously low. Collected taxes and royal proceeds accumulating in the Americas were desperately needed. It was paramount that the 1622 fleet successfully make the long and dangerous voyage. The government’s creditors were impatient, and the king’s share of the treasure would keep them at bay a bit longer. It might even convince them to extend more badly needed funds for the war effort.

Despite the urgent need, the fleet could only begin its voyage in late spring or early summer. The Atlantic is hospitable to sailing ships only a few months each year. Winter storms in the North Atlantic made the trip to the Americas dangerous if taken before early spring. And from June to October, the South Atlantic routes traveled by the convoys on their journey back to Spain from Havana were racked by hurricanes. Lashed by mammoth seas, ships ambushed by a hurricane could neither steer nor sail. They could merely run in front of the wind and hope it blew itself out before the ship was swamped or her hull was torn open on a shallow coral reef. The later in the summer the fleets sailed from Havana, the more likely they were to encounter a major hurricane. If the convoys waited out the hurricane season in the harbor at Havana – leaving in late October or November-they risked sailing into the violent winter storms of the North Atlantic.

This year, the flotas left Spain separately: the Tierra Firme fleet, including the heavily-armed Nuestra Senora de Atocha, left March 23, 1622, arriving at Portobello on the Isthmus of Panama on May 24. Seven Guard galleons, including the Santa Margarita, sailed from Cadiz on April 23, arriving at the island of Dominica on May 31. There, 16 smaller vessels fanned out to pick up goods from around the Caribbean while the Guard galleons sailed to Cartagena, Colombia to unload their outbound cargos, arriving on June 24. Finding that much of the silver and gold to be shipped back to Spain had not yet arrived at the port for loading, the Guard galleons sailed for Portobello, joining the Tierra Firme fleet there on July 1.

The commander of the Guard fleet, the Marquis of Cadereita, was told that 36 Dutch warships were at the Araya salt-pans on the north coast of South America. For extra protection he commandeered a privately owned galleon, Nuestra Senora del Rosario, to his Guard fleet, bringing it up to its full authorized strength of eight ships.

The ships left Portobello, arriving back in Cartagena on July 27. After receiving more cargo, they sailed for Cuba on August 3. Poor sailing conditions delayed their arrival, and the fleet didn’t reach Havana until August 22. The presence of so many Dutch raiders must have weighed heavily on the Marquis’ mind. The New Spain fleet had collected its cargo in Mexico and waited in Havana for the rest of the fleets. Now, as the most dangerous part of the hurricane season neared, its commander impatiently requested permission to sail for Spain. The Marquis assented, but directed that the bulk of the bullion shipped back under the protection of the big cannons of the Guard fleet.

The Marquis split his fleet into two parts. He would sail in the capitana, the lead ship, Nuestra Senora de Candeleria. Much of the one and a half million pesos worth of treasure-aboard worth today perhaps $400 million-was assigned to the Santa Margarita and the new ship, the Nuestra Senora de Atocha. The Atocha had been built in the Havana shipyard and, sure to bring her good luck, was named for the most revered religious shrine in Spain. Just in case the Almighty’s providence didn’t extend to sinking Dutch warships, the Atocha was fitted with 20 bronze cannons. This strong ship was to be the almiranta, sailing last to protect the slow, lumbering merchant ships in the rear of the flota. The Tierra Firme and Guard ships – 28 vessels in all-departed from Havana on September 4, six weeks behind schedule.

Neither God’s providence nor gunpowder could protect the ships from the weather.

On September 5, the fleets were overtaken by a rapidly-moving hurricane. As dawn streaked the horizon, it brought dread to the more experienced sailors. The gale force winds, rising out of the northeast, quickly increased. The gusts raked the surface of the northward-flowing Gulf Stream, piling up huge seas in front of the ships. Aboard the Atocha, the chief pilot lit a lantern as clouds and rain blackened the sky. Ahead, the lead galleons were already out of sight. The merchant ships sailing close by the almiranta were themselves hidden by rain as the storm swept by. Crewmen scrambled into the rigging to take in sail. As they hung from this fragile rope spider’s web high above the deck, the ends of the yard arms dipped into the ocean as the ship rolled violently. Frothing green water roared across the deck. Just before darkness, a veil of spray closed around the seasick passengers and crew of the Atocha. They watched in horror as the tiny Nuestra Senora de la Consolacion, wallowing in the mammoth seas, simply capsized and disappeared.

That night, the wind shifted, coming out of the south. The hurricane now hurled the fleet north toward the Florida reef line. Before daylight, the Marquis’ ship-the Candeleria-and 20 other vessels passed to the west of a group of rocky islands, the Dry Tortugas. Beyond the reefs of the Straits of Florida, they rode out the winds in the safe, deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico. Behind them, they’d left several small merchant vessels on the bottom in deep water. At least four ships, including the Atocha and Santa Margarita, were swept headlong into the Florida Keys. Near a low-lying atoll fringed with mangroves, 15-foot rollers carried the Margarita across the reef, grounding her in the shallows beyond. As she crossed the reef, her commander, Captain Bernardino de Lugo, looked to the east. There he saw the Atocha.

With crew and passengers huddled, praying below deck, the Atocha approached the line of reefs dividing safe, deep water from certain death. The frenzied crew dropped anchors into the reef face, hoping to hold the groaning, creaking galleon off the jagged coral. A wave lifted the ship, and, in the next instant, flung it down directly onto the reef. The main mast snapped as the huge seas washed Atocha off the reef and beyond, trailing her broken mast. Water poured through a gaping hole in the bow, quickly filling the hull with water. The great ship slipped beneath the surface, finding bottom 55 feet below; only the stump of the mizzenmast broke the waves. Of the 265 persons aboard, 260 drowned. Three crewmen and two black slaves clung to the mast until they were rescued the next morning by a launch from another fleet ship, the Santa Cruz.

The lost ships of the 1622 treasure fleet lay scattered over 50 miles stretching from the Dry Tortugas eastward to where the Atocha slipped beneath the water. About 550 people perished along with a total cargo worth more than 2 million pesos.

You may be interested in following coins

2025-06-18

- Live Coin Catalog's improvements / coins grouping

22 coins were grouped from 2025-06-11 to 2025-06-18

One of them is:

2 1/2 Cent Netherlands

group has 18 coins / 14 prices

⇑

NETHERLANDS 2-1/2 Cents 1904 - Copper - Wilhelmina - XF/aUNC - 3791 *

2025-05-25

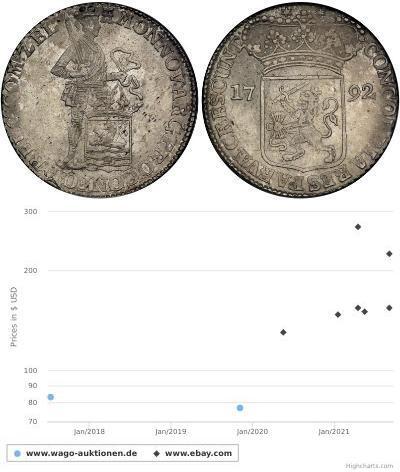

- Historical Coin Prices