10 Centesimo Kingdom of Italy (1861-1946) Copper Umberto I (1844-1900)

1893, Kingdom of Italy, Umberto I. Beautiful Copper 10 Centesimi Coin. XF-AU!

Mint Year: 1893 Reference: KM-27.1, Pagani-616. Condition: A nice XF-AU! Denomination: 10 Centesimi Mint Place: Birmingham (B/I) Material: Copper Diameter: 30mm Weight: 9.82gm

Obverse: Head of Umberto I left. Legend: UMBERTO I – RE D’ITALIA

Reverse: Star above value (10), denomination (CENTESIMI) and date (1893). All within wreath. Comment: Mint initials (B/I) of the Birmingham mint below!

Umberto I or Humbert I (Italian: Umberto Ranieri Carlo Emanuele Giovanni Maria Ferdinando Eugenio di Savoia, English: Humbert Ranier Charles Emmanuel John Mary Ferdinand Eugene of Savoy; 14 March 1844 – 29 July 1900), nicknamed the Good (in Italian il Buono), was the King of Italy from 9 January 1878 until his death. He was deeply loathed in far-left circles, especially among anarchists, because of his conservatism and support of the Bava-Beccaris massacre in Milan. He was killed by anarchist Gaetano Bresci two years after the incident.

The son of Vittorio Emanuele II and Archduchess Maria Adelaide of Austria, Umberto was born in Turin, which was then capital of the kingdom of Sardinia, on 14 March 1844. His education was entrusted to, amongst others, Massimo Taparelli, marquis d’Azeglio and Pasquale Stanislao Mancini.

From March 1858 he had a military career in the Sardinian army, beginning with the rank of captain. Umberto took part in the Italian Wars of Independence: he was present at the battle of Solferino in 1859, and in 1866 commanded the XVI Division at the Villafranca battle that followed the Italian defeat at Custoza.

On 21 April 1868 Umberto married his first cousin, Margherita Teresa Giovanna, Princess of Savoy. Their only son was Victor Emmanuel, prince of Naples; later Victor Emmanuel III of Italy.

Ascending the throne on the death of his father (9 January 1878), Umberto adopted the title “Umberto I of Italy” rather than “Umberto IV” (of Savoy), and consented that the remains of his father should be interred at Rome in the Pantheon, rather than the royal mausoleum of Basilica of Superga.

While on a tour of the kingdom, accompanied by Premier Benedetto Cairoli, he was attacked by an anarchist, Giovanni Passannante, during a parade in Naples on 17 November 1878. The King warded off the blow with his sabre, but Cairoli, in attempting to defend him, was severely wounded in the thigh. The would-be assassin was condemned to death, even though the law only allowed the death penalty if the King was killed. The King commuted the sentence to one of penal servitude for life, which was served in conditions in a cell only 1.4 meters high, without sanitation and with 18 kilograms of chains. Passanante would later die in a psychiatric institution, after torture had driven him insane. The incident upset the health of Queen Margherita for several years.

In foreign policy Umberto I approved the Triple Alliance with Austria-Hungary and Germany, repeatedly visiting Vienna and Berlin. Many in Italy, however, viewed with hostility an alliance with their former Austrian enemies, who were still occupying areas claimed by Italy.

Umberto was also favorably disposed towards the policy of colonial expansion inaugurated in 1885 by the occupation of Massawa in Eritrea. Italy expanded into Somalia in the 1880s as well. Umberto I was suspected of aspiring to a vast empire in north-east Africa, a suspicion which tended somewhat to diminish his popularity after the disastrous Battle of Adowa in Ethiopia on 1 March 1896.

In the summer of 1900, Italian forces were part of the Eight-Nation Alliance which participated in the Boxer Rebellion in Imperial China. Through the Boxer Protocol, signed after Umberto’s death, the Kingdom of Italy gained a concession territory in Tientsin.

The reign of Umberto I was a time of social upheaval, though it was later claimed to have been a tranquil belle époque. Social tensions mounted as a consequence of the relatively recent occupation of the kingdom of the two Sicilies, the spread of socialist ideas, public hostility to the colonialist plans of the various governments, especially Crispi’s, and the numerous crackdowns on civil liberties. The protesters included the young Benito Mussolini, then a member of the socialist party.

During the colonial wars in Africa, large demonstrations over the rising price of bread were held in Italy and on 7 May 1898 the city of Milan was put under military control by General Fiorenzo Bava-Beccaris, who ordered the use of cannon on the demonstrators; as a result, about 100 people were killed according to the authorities (some claim the death toll was about 350); about a thousand were wounded. King Umberto sent a telegram to congratulate Bava-Beccaris on the restoration of order and later decorated him with the medal of Great Official of Savoy Military Order, greatly outraging a large part of the public opinion.

To a certain extent his popularity was enhanced by the firmness of his attitude towards the Vatican, as exemplified in his telegram declaring Rome “untouchable” (20 September 1886), and affirming the permanence of the Italian possession of the “Eternal City”.

Umberto I was attacked again, by an unemployed ironsmith, Pietro Acciarito, who tried to stab him near Rome on 22 April 1897.

Finally, he was murdered with four revolver shots by the Italo-American anarchist Gaetano Bresci in Monza, on the evening of 29 July 1900. Bresci claimed he wanted to avenge the people killed during the Bava-Beccaris massacre.

He was buried in the Pantheon in Rome, by the side of his father Victor Emmanuel II, on 9 August 1900. He was the last Savoy to be buried there, as his son and successor Victor Emmanuel III died in exile.

A newspaper report of Bresci’s attack was carried and frequently read by the American anarchist Leon Czolgosz; Czolgosz used the assassination of Umberto I as his inspiration to murder U. S. President William McKinley in September, 1901 under the banner of Anarchism.

(3205 X 1576 pixels, file size: ~978K)

Posted by: anonymous 2024-07-30

1893, Kingdom of Italy, Umberto I. Beautiful Copper 10 Centesimi Coin. XF-AU! Mint Year: 1893 Reference: KM-27.1. Condition: A nice XF-AU! Denomination: 10 Centesimi Mint Place: Birmingham (B/I) Material: Copper Diameter: 30mm Weight: 10gm Obverse: Head of Umberto I left. Legend: ...

(1537 X 738 pixels, file size: ~282K)

Posted by: anonymous 2019-03-18

1893, Kingdom of Italy, Umberto I. Beautiful Copper 10 Centesimi Coin. XF-AU! Mint Year: 1893 Reference: KM-27.1. Condition: A nice XF-AU! Denomination: 10 Centesimi Mint Place: Birmingham (B/I) Material: Copper Diameter: 30mm Weight: 9.82gm Obverse: Head of Umberto I left. ...

(1365 X 664 pixels, file size: ~207K)

Posted by: anonymous 2019-05-15

1894, Kingdom of Italy, Umberto I. Nice Copper 10 Centesimi Coin. XF! Mint Year: 1894 Reference: KM-27.1. Denomination: 10 Centesimi Condition: Light deposits, otherwise XF! Mint Place: Birmingham (BI) Material: Copper Diameter: 30mm Weight: 9 ...

(1200 X 559 pixels, file size: ~156K)

Posted by: anonymous 2015-08-24

UMBERTO I (1878-1900) 10 Centesimi 1894 Roma. Pag. 615 MIR 1106c Cu Rara FDC

(1205 X 600 pixels, file size: ~174K)

Posted by: anonymous 2015-03-06

Italy. 10 Centesimi, 1894-BI. KM-27.1; Pagani-616. Umberto I. NGC graded MS-64 Brown. Estimated Value $75 - 100. Categories:

|

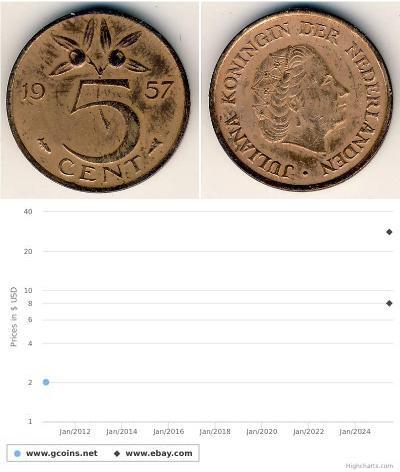

5 Cent Netherlands

group has 11 coins / 8 prices

⇑

-500-250-B3sKbzbirLUAAAFLIDCgLg7U.jpg)

-300-150-kmGsHgTyS7kAAAGRVz8fqgXa.jpg)

-300-150-1oMmaIlrgtMAAAFpqeKKgY9m.jpg)

-300-150-Js50WDeKdigAAAFqDm2VQLoU.jpg)

-300-150-BwEKX9ISsUsAAAFasmdMgKdu.jpg)

-300-150-pWEKbzbiXrgAAAFPYcxtcWHT.jpg)

-300-150-B3sKbzbirLUAAAFLIDCgLg7U.jpg)